How to Achieve Your Goals, Step 1: The Push and Pull of Feedback Loops

/Setting and achieving goals seems straightforward enough in principle: figure out what you’d like to have or what kind of person you’d like to be, and then make concerted effort in that direction until you get there.

This is how it's often framed in our society, anyway. The logical conclusion is that if you want it badly enough, and try hard enough, you should be able to achieve your goal.

But this oversimplified view of achievement doesn't allow for many interpretations when you fall short. There must be something wrong with you. You must not have enough willpower, or maybe you don’t even have the skills or other qualities it takes to achieve your goal. So, either the goal—or you!—were ill-conceived. You either need to aim lower, or get used to your dreams appearing as gauzy fantasies rather than anything you could ever actually touch.

But there’s more to the science of setting and achieving goals than just brute force and perseverance. Here we’ll start to explore a framework that you can use to figure out why and how you make progress, or don’t, and what you can do to take a fresh approach to the changes you want to make.

Feedback Loops

At its most fundamental level, achieving a goal involves gauging your current state, identifying a change you'd like to make, making an adjustment, and repeating as necessary.

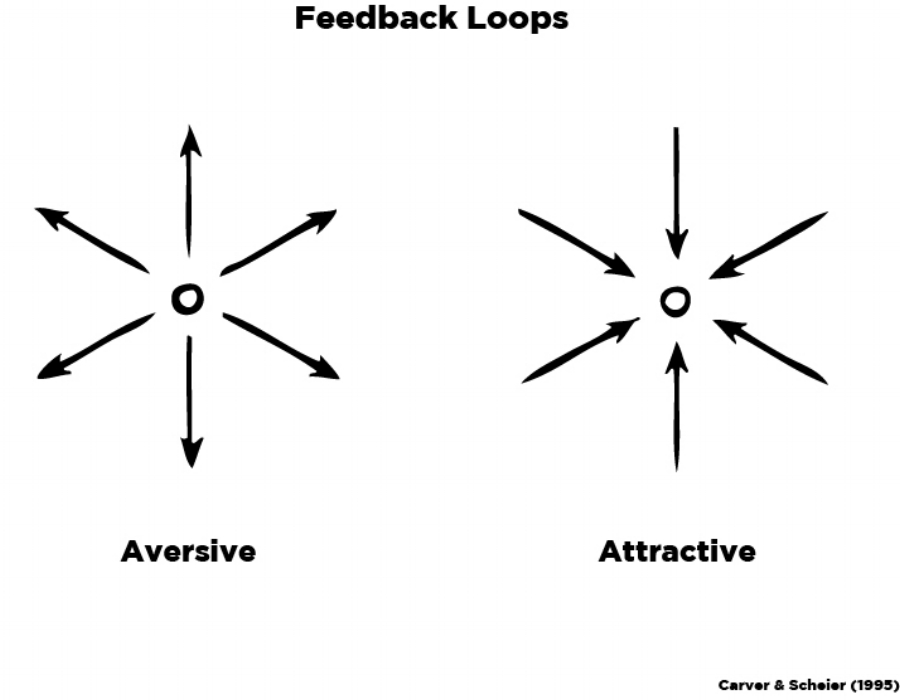

This process is called a feedback loop, and there are two types of them: positive and negative. The terms positive and negative don't have to do with whether your efforts, goals, or outcomes are good or bad; they describe the type of motivation involved.

Negative feedback loops operate to reduce the distance between the current state and a desired state (or “reference value"), like the way the thermostat in your home or office registers the temperature of the room, compares it to the desired temperature you’ve set, and blows hot or cold air to bring the two closer together.

The positive feedback loop aims to increase the distance between the current state and an undesired state (a different kind of reference value).

These terms can be confusing because we usually employ negative feedback loops to pursue something we want, and positive feedback loops to avoid things we don't want.

One way of visualizing the difference between the two is to recall your days of playing with magnets. When you place the same-polarity sides of two magnets together, they push each other away, and they aren’t careful about it. All they want to do is be further away from each other, and if you try to push them together, they seem to squirm around any which way they can, even harder, in order to avoid each other. It’s a generalized repulsion.

This is a positive feedback loop. The negative feedback loop is like when you present opposite poles to each other, and there is no confusion: they latch on to each other right away.

So, both types of feedback loops involve a motivational force: in the case of negative feedback loops the energy is an attractive pull, while the positive loop is energized by an aversive thrust. (For clarity's sake, I'll call them "attractive" and "aversive" feedback loops from now on.)

This makes a big practical difference, because there are many ways of not having a certain state or quality, but only one way of having it. If you just set your thermostat to “anything but 78°” the system doesn’t know whether to make it warmer or cooler. If you head to the airport for a vacation and say "take me anywhere but here," there's no telling where you'll end up.

In a similar way, operating with only the goal of avoiding an outcome could leave you floating aimlessly or propelled toward a different destination, but not necessarily a better one.

Joining Feedback Forces

Social psychologists note that aversive feedback loops by themselves aren't very common in nature because of this inherent instability. Nature abhors a vacuum, so the absence of an attractive goal tends not to last.

In fact, people's aversive feedback loops often operate in tandem with a complementary attractive one: they're trying to move away from one thing and toward something else at the same time.

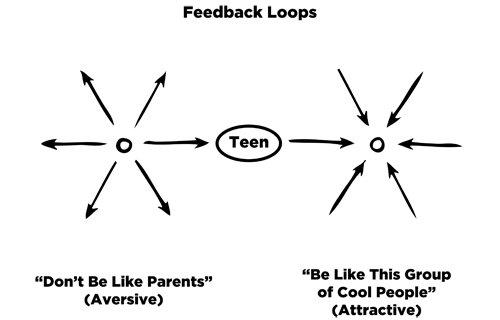

Consider a rebellious teenager, determined to be unlike his parents. He can achieve this in any number of ways, but being an army of one, without social support, isn’t terribly satisfying or stable.

So teenagers rebelling from their parents usually find a new group to identify with, and seek to narrow the gap with that group while widening the one with their parents.

Complementary feedback loops are also at work when a person's political leanings reflect both an attraction to one set of beliefs and others who share them (an attractive feedback loop) and an aversion to a political party or figure whose whose beliefs she finds offensive (an aversive feedback loop).

You might think of an aversive feedback loop as blasting you off into space from an unpleasant planet, and the attractive feedback loop as the gravitational pull of the one you’d like to land on. In other words, the attractive goal provides additional energy and direction to your travels.

We operate in pursuit of countless goals each day, of course. They include the most fleeting short-term goals (like shifting in your seat to move away from discomfort and toward comfort), to getting to work on time, trying to change personality traits, wanting to be happy and fulfilled in our lives, or rich, or to leave a legacy of some kind.

We create some goals on the fly and deliberate about others. Some were born long ago, in our childhood, and others are even more primordial. And with each goal comes at least one feedback loop, and often more than one.

If you step back and look at the totality of your life in all of its dimensions—psychological and physical health, relationships, career, etc.—you can see that you have a nearly infinite number of positions you currently occupy, interacting through attractive or repulsive forces with others that you do or don’t want to occupy.

You hold the universe of your goals within a vast web of attractive and repulsive forces of varying magnitudes, and some goals you have may motivate more than one dimension of your life. (For instance, maybe your desire to avoid being greedy motivates your behavior in your relationships as well as in your career.)

Now, there is more to the science of goal achievement than this. In future articles, I’ll go into some questions that may have occurred to you, like why is it that sometimes it feels like no movement is taking place in any direction?

Why it is that sometimes you’re making progress toward a goal, but still aren’t satisfied? Or, what happens when you've achieved your goal? Then what—do all the forces just stop? And why can it be so hard to maintain the progress you’ve made sometimes?

But for now, the important take-away is that the status of any dimension of your life can be characterized by at least two points: your current position and the thing(s) you'd like to achieve or avoid.

If you’re like most people, you concern yourself mostly with the goal-setting and adjustment-making steps of the feedback loop, but for now, resist that urge. The best first step is to make an accurate, honest assessment of your current position as it is right this moment and identify the attractive and aversive forces that influence you.

You can start by identifying the feedback loops you have in those areas of your life that you’d like to work on. What do you feel motivated to avoid, and what are you trying to gain?

It may take a little digging, because you may have been set in motion a long time ago, and also because you may not be consciously aware of them right now. (Helping people see what makes them tick is one of the ways I serve my personal coaching and executive coaching clients.) It can be helpful to take a piece of paper and start to draw them out. (I’ve included a basic example here; yours will look different, of course.)

Whether you feel stuck in place or like you're zooming around out of control, you’re being affected by all of your feedback loops right now and they, along with future ones yet to be created, will determine what direction you will move in next.

The more thorough your assessment, the better able you’ll be able to combine and leverage these attractive and repulsive forces to help you make the progress you're looking for.

Next: How to Achieve Your Goals, Step 2: Tackling the Rogue Aversion